Sorting Japanese is not only difficult—it’s an unsolved problem. This seems hard to believe if you are not familiar with the complexities of processing Japanese digitally. But what is trivially easy in English is impossible in Japanese, even with the amount of computer power we have available today.

The problem comes from the complex nature of written Japanese. Contrast it with English, which only has 26 letters: a comes before b; b comes before c; and so on. On the other hand, Japanese not only has thousands of characters, it also has four different kinds of written characters. But this is only the beginning of the difficulty. The unique nature of kanji characters and their associated pronunciations is the language feature that makes Japanese unsortable.

Let’s work our way through the complexities to understand why Japanese cannot be sorted.

A Simple Sort

Let’s do a simple sort of a list of English words. Here I have a list of characters from the video game Street Fighter.

Let’s put this list through a simple sort function using PHP.

<?php

$names = array (“Ryu”, “Ken”, “Chun-Li”, “Yun”);

sort ($names);

foreach ($names as $name) {

echo “$name<br/>”;

}

?>

Here is the result:

This is the result we expect—it’s in alphabetical order. A computer can easily sort English in alphabetical order because there are simple rules. C comes before K; K comes before R; and R comes before Y. You should have learned this in the first grade.

Now let’s start looking at the complexities of Japanese, and see why sorting does not work as easily.

Multiple Character Sets

Japanese has four different character sets in the written language. Don’t worry about why there are four different types of characters, just know that there are.

- Hiragana alphabet — ひらがな

- Katakana alphabet — カタカナ

- Kanji characters — 漢字

- ABC alphabet — abc

Here is where the difficulty comes in: each character set has characters with the same pronunciations as characters in the other sets. On top of that, all four character sets are written together to form what is modern written Japanese. If you only had to deal with one character set at a time (ignoring kanji for the moment, we will get to that later), you could sort Japanese automatically just like English. Hiragana sorts just fine; katakana sorts just fine; and the ABC alphabet sorts just fine. But, in combination, it is not clear how you would sort these.

I should note that there are two different alphabetical sorting orders in Japanese. For this article I am going to use the a i u e o (あいうえお) sort order.

Sorting Settings

Now let’s look at an example of sorting mixed character sets. Again, using PHP.

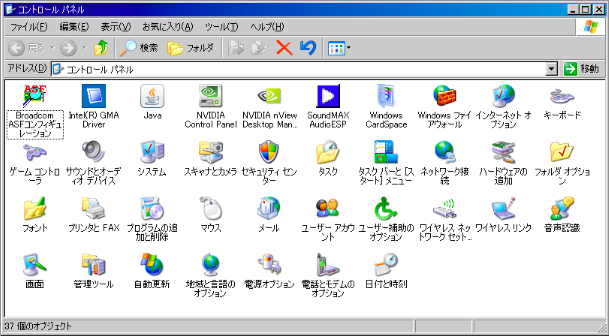

<?php

setlocale(LC_ALL, ‘jpn’);

$settings = array (“システム”, “画面”, “Windows ファイウォール”,

“インターネット オプション”, “キーボード”, “メール”, “音声認識”, “管理ツール”,

“自動更新”, “日付と時刻”, “タスク”, “プログラムの追加と削除”, “フォント”,

“電源オプション”, “マウス”, “地域と言語オプション”, “電話とモデムのオプション”,

“Java”, “NVIDIA”);

sort ($settings);

foreach ($settings as $setting) {

echo “$setting<br/>”;

}

?>

Here is the result.

- Java

- NVIDIA

- Windows ファイアウォール

- インターネット オプション

- キーボード

- システム

- タスク

- フォント

- プログラムの追加と削除

- マウス

- メール

- 地域と言語のオプション

- 日付と時刻

- 画面

- 管理ツール

- 自動更新

- 電源オプション

- 電話とモデムのオプション

- 音声認識

Take a look at what happened with this sort. The first three strings start with characters of the alphabet, and were sorted as we expect. The next eight strings are in katakana, and they are sorted correctly according to the Japanese a i u e o sort order. The rest of the strings all start with kanji and are not sorted in any way that makes sense to a human.

So what is going on here? In this case, it seems that PHP is using the character code to determine the sort order. This works fine with alphabets like English, or even the Japanese katakana, because the character codes go in order with the sort order. But the character codes do not go in order when mixed with other character sets. In this example you can see ABC and katakana are separated. Kanji are then separated from katakana. There were no hiragana in this list but they would do the same. Sort order by character code works fine for alphabets when the alphabets are by themselves. But once you mix alphabets together, you cannot have any sensible sorting order by doing it that way.

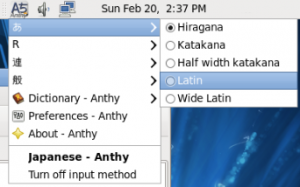

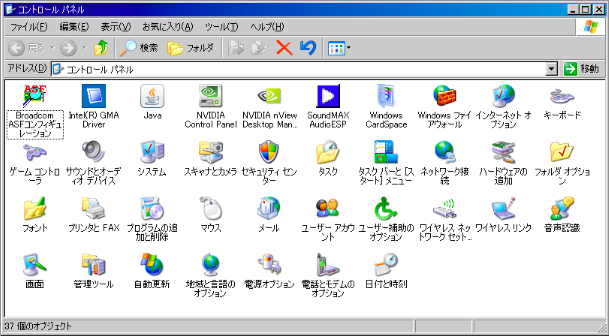

An observant reader might have noticed what these items in our list are: Control Panel items in Windows XP. It’s clear that PHP’s sort function can’t sort this properly. But what about Windows XP Japanese edition?

Microsoft seems to have the same problem. They do alright with sorting each character set individually. But they don’t seem to be able to integrate the character sets together like a Japanese user would expect. It’s OK, I don’t expect Microsoft to be able to solve such a hard problem.

Sorting Names

Let’s look at another example to show what happens when you have all four character sets sorted together. Here we have two names, both written four different ways—using each character set: ABC alphabet, hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

Ayumi、 あゆみ、アユミ、歩美

Tanaka、たなか、タナカ、田中

It is very possible to have different people with the same name write their name in different character sets. The traditional way of writing the Japanese name of Ayumi would be written in kanji; a modern, stylish way would be to write it in hiragana, and a second generation Japanese-American might write their name in katakana or the alphabet.

Put these names into the same PHP sort function and look what happens.

<?php

setlocale(LC_ALL, ‘jpn’);

$names = array (“Ayumi”, “アユミ”, “あゆみ”, “歩美”,

“Tanaka”, “タナカ”, “たなか”, “田中”);

sort ($names);

foreach ($names as $name) {

echo “$name<br/>”;

}

?>

Here is the result:

- Ayumi

- Tanaka

- あゆみ (Ayumi)

- たなか (Takana)

- アユミ (Ayumi)

- タナカ (Tanaka)

- 歩美 (Ayumi)

- 田中 (Tanaka)

Within each character set Ayumi is sorted before Tanaka, which is correct for the ABC, hiragana, and katakana alphabets. The kanji pair had a 50/50 chance of being right. But as you can see, the different character sets are not integrated together. If these were all names in your phone’s contact list or your Facebook friends list, you would expect all of the Ayumis and Tanakas to be listed together.

The ABC, hiragana, and katakana alphabets can be sorted—although which character set of Ayumi gets sort preference is a whole other issue—once that preference is agreed upon, sorting can be done just as easily as English.

Kanji — The Real Problem

The real problem with sorting Japanese text is kanji. Kanji aren’t just difficult for students of Japanese to make sense of, they are literally impossible for computers to process with the same intelligence as a human. The reason for this is the following:

Kanji have multiple pronunciations, determined by the context in which it appears.

This fact keeps students up nights studying for years trying to remember how to pronounce kanji right. And it also makes our sorting problem extremely nontrivial. We sort things in language by the pronunciations. Up until now we were dealing with letters. ABC, hiragana, katakana—these are all letters which a single pronunciation. There is only one place they can go.

Kanji on the other hand all have multiple pronunciations. Some have over ten! Only from the context in which the kanji appears do you know how to pronounce it. Our simple sorting problem has now turned into a natural language processing problem.

Here is an example:

私は私立大学で勉強しています。

Here the kanji 私 is used in two different contexts. The first usage, is 私 (watashi). The second usage is part of the compound word 私立大学 (shiritsu daigaku). Using the Japanese sort order, these words should be sorted like this:

A second year Japanese student could figure this out. For a computer, this is a very difficult problem.

Here is another, more extreme example.

There are four Japanese women whose names you have to sort: Junko, Atsuko, Kiyoko, and Akiko. This does not seem difficult, until they each show you how they write their names in kanji:

- 淳子 (Junko)

- 淳子 (Atsuko)

- 淳子 (Kiyoko)

- 淳子 (Akiko)

As you can see, this is rather troublesome. This comes back to kanji having multiple pronunciations. If this was for an address book of your phone contacts for example, you would want Atsuko and Akiko listed with the A names like Ayumi and Akira. But you would not want Junko and Kiyoko listed there.

And this problem is not limited to names. Regular, everyday words also have multiple pronunciations. For example, 故郷 (ふるさと、こきょう), 上手 (じょうず、じょうて、うわて、かみて…) etc.

So how do we deal with this? They have phones and social networking Web sites in Japan with sorted contact lists, so how can we sort these words properly?

The Wrong Way – Using IME Input

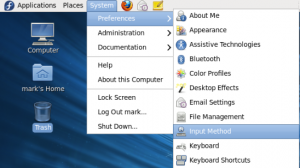

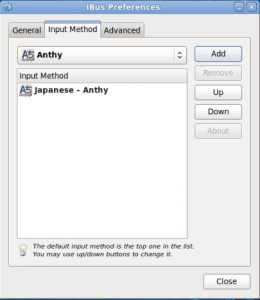

First, let’s look at a good try, but failed attempt at Microsoft to try to solve this problem. What good would Excel be if you could not sort on columns and rows. Microsoft clearly understands the issue with sorting Japanese—they just didn’t think through the solution thoroughly.

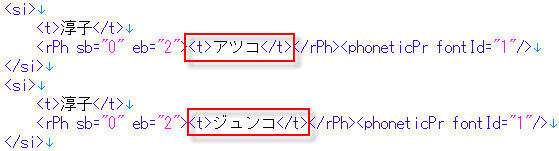

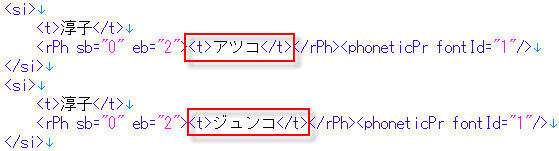

What Microsoft does in Excel is to capture the input the user types to get the kanji character. For example, if you typed Junko to get 淳子, it will save that input string as meta data in the background. When it is time to sort, it sorts on the input pronunciation meta data rather than the kanji that are displayed. You can actually see what the meta data looks like in Excel 2003 if you save as XML.

You can see the kanji 淳子 is in two different rows, but the input used to get them was different, Atsuko and Junko, so those are saved as meta data to assist with sorting later on.

The problem with this approach is it doesn’t take into account of how people actually interact with computers using a Japanese IME system. Japanese input works with a dictionary of possible kanji conversions based on what has been input. But not every word or name is in that dictionary. Sometimes you have to type each kanji individually or use a totally different pronunciation to get the kanji you want to show up. This results in the wrong pronunciation being saved as meta data, and sorting will not work as expected.

This system also doesn’t work with cutting and pasting text from other sources, as well as any sort of CSV or database import, etc. This was a good try by Microsoft to solve this problem, but it just doesn’t work.

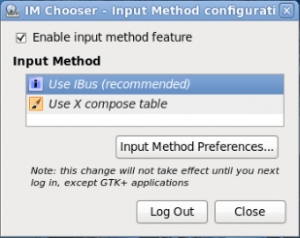

The Right Way – Ask the User

A computer simply cannot guess the correct pronunciation of kanji, even if it logs the users input, because that might not even be correct. The easiest way to solve this problem is just ask the user for the pronunciation! Most software developed in Japan uses this approach.

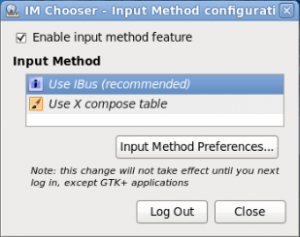

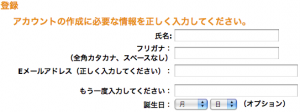

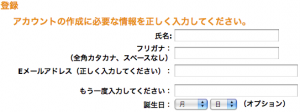

Let’s look at this approach done correctly: Amazon.com. Let’s look at their new user registration First, notice the fields in the English version of this screen.

Now look at the Japanese version of this screen.

As you can see, the Japanese version has an extra field. This is for the user to enter the pronunciation of their name in katakana. This way, Amazon has their name in kanji, and the correct pronunciation to go with. They can now sort their user information correctly. This is the approach that most Japanese software takes. It is an extra step, but it solves the problem.

The big takeaway from this is that you cannot just translate software, or even a Web site, and expect it to work. Something as simple as registering a new user has to be completely reworked. In the case of a simple Web site, you will need to redo not only the Web interface, but also the database back end and the code to interface with the database and Web site generation. Localizing a site into Japanese is much more complicated than other languages because of the extra functionality that is required.

While Amazon.com does do the interface and programming localization correct, they do have something on their site that isn’t localized for the Japanese audience: Their logo.

In English, the logo goes with their saying: “Everything from A to Z.” This is indicated by the arrow. But in Japan, and any other country that doesn’t use English, A and Z aren’t always the first and last letters of the alphabet. The A to Z thing works in English because the name Amazon has A and Z in it. But in other countries, they might not have any idea why there is an arrow under the Amazon logo.

Final Thoughts

Sorting in Japanese is hard. Without user input, it is impossible in some contexts to know how to sort some Japanese words. People developing and localizing software need to understand these issues. But regarding the general problem of sorting Japanese when you don’t have user input to give the pronunciation, there may not be a way to automate this until computers can understand language as well as a native Japanese person. For a computer to understand Japanese is far more complex than most other languages. You can see this first hand by using machine translation software and comparing Japanese to something like French.

I think this is an interesting problem. This goes beyond just sorting. How can you expect a machine translation program to work if it doesn’t even know the pronunciation of a word—something that can be key to understanding what that word is. I can imagine even statistical machine translation being confused, especially with names.

Japanese is an interesting language, and processing it with computers is even more interesting.